African American Or Other? Selecting Your Race, Ethnicity On U.S. 2020 Census Form

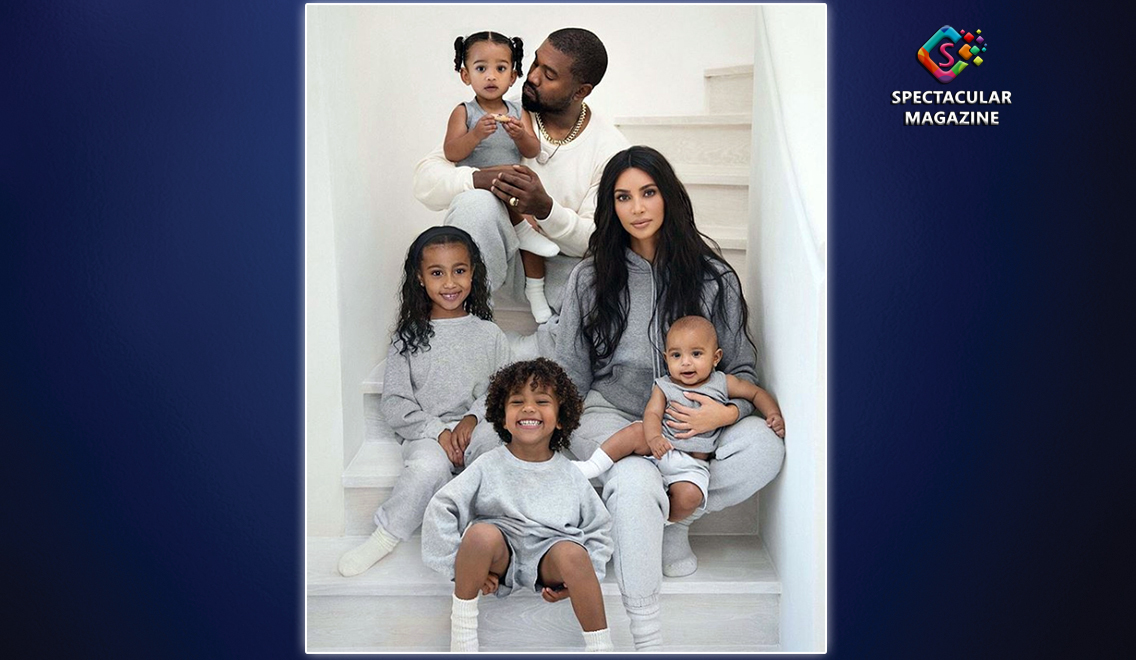

Kim Kardashian West will likely check “Black or African American” on the U.S. 2020 Census form when marking the race of her children.

In several interviews with various media outlets, the famous media personality and businesswoman, who lives in the San Fernando Valley near Calabasas, has said she’s very conscious of race when it comes to her and rapper Kanye West’s four children.

Kardashian, who is half-White and half-Armenian, has said she identifies the race of her children as “Black” and says the advocacy she has recently been involved in: addressing racial inequities in the criminal justice system—is partly inspired by the race of her children.

On this year’s census form, Kardashian’s other option for checking the race box to identify her children would be to select “Other.” That’s if she chooses to count them as biracial or mixed race.

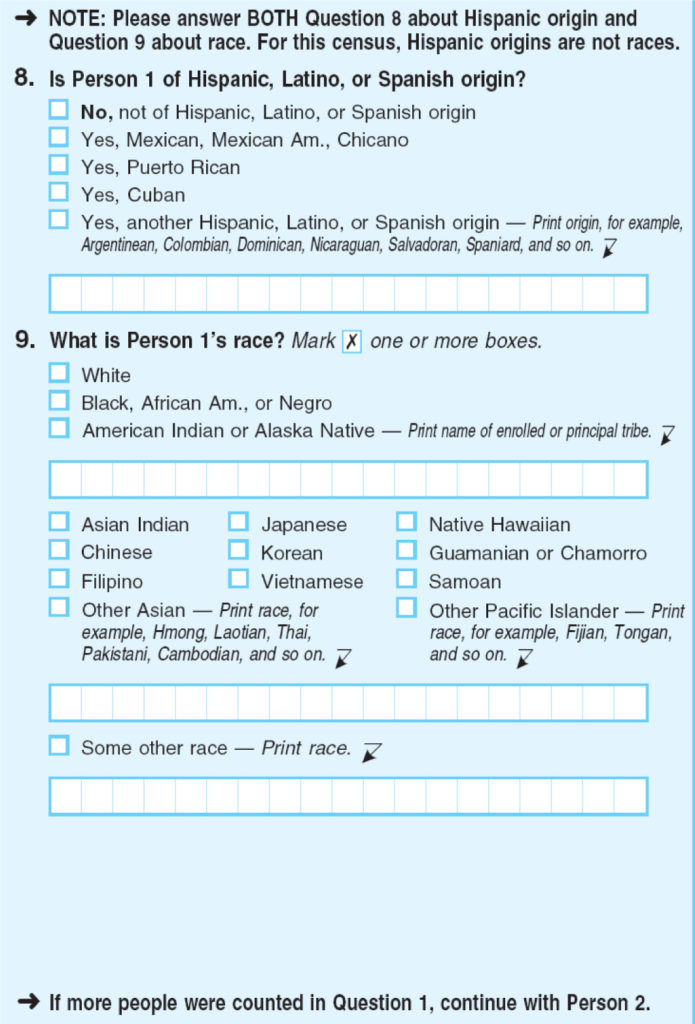

Race and ethnicity have often been—and continue to be—controversial and misunderstood census categories. Experts suggest that some people might be confused about the difference between the two.

On the 2020 census forms, there will be six ways people can identify their race: American Indian or Alaska Native; Asian; Black or African American; White; Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander; and Other.

On the 2020 census forms, there will be six ways people can identify their race: American Indian or Alaska Native; Asian; Black or African American; White; Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander; and Other.

Options will also be available for respondents to include an ethnic identification, too. For instance, a Trinidadian-American of African descent may select “Black or African American” under the racial category and write in “Trinidadian” under the ethnic category.’

According to the Census Bureau, “Overlap of race and Hispanic ethnicity is the main comparability issue.” For example, the U.S. Census Bureau includes Black Hispanics in both the number of Blacks and in the number of Hispanics.

Dr. Walter Hawkins, former California State University San Bernardino Director of Research and Policy Analysis, helped clear some of that confusion by detailing the numerous ways people can self-identify on US 2020 Census forms, mentioning the “100 percent count.”

“Under the Census Bureau, in order to get the 100 percent count, they have to use what’s called the ‘Hispanic exclusive method’ because a person who is Hispanic can be any race. So, if you do not take that into consideration, you end up with over 100 percent,” said Hawkins.

Hawkins noted that much of the complication with racial self-identification originated from an old census rule called “head of household.”

“If you marked ‘Black,’ your whole house was Black. And if you marked ‘White,’ your whole house was White,” Hawkins said.

Data collected during national censuses, which the federal government conducts every 10 years, directly impacts not only the availability but also the quality of services in communities, according to Dr. Anthony Asadullah Samad, Executive Director of the Mervyn Dymally African American Political and Economic Institute (MDAAPEI) at California State University Dominguez Hills.

Inaccurate census counts can lead to billions of dollars lost in government funding for states and local communities. That loss of cash can be critical for already under-served neighborhoods that rely on federal and state tax dollars for social programs, healthcare, infrastructure, schools, and other local public services. Census counts also determine the number of representatives a state is allotted in the US Congress.

“Cultural identity is important to every community. First, in understanding presence. Second, in understanding population growth,” Samad said. “Every ethnicity faces this challenge in the upcoming census, including Latinos and Asian Pacific Islanders, because demographic descriptions speak to a particular community’s service needs.”

According to Samad, African Americans have been at a disadvantage in this regard.

“For the last three censuses, there have been African American undercounts,” Samad said. “The only ethnicity with larger undercounts have been Native Americans, largely due to their populations being on sovereign lands that limit census-taker access.”

According to the Census Bureau, the population of Black or African American people who did not identify with any other race in 2018 counted for 6.5 percent of the overall population in California. Whereas, the population of people who identified as mixed-race made up 3.9 percent of the state’s overall population.

The mixed population counts as its own category, making it unclear how many of these people have African lineage.

Samad pointed to another factor that might skew the amount of African Americans being accounted for in the Census: Fear.

“Black people have legitimate fears for sharing information with the federal government for numerous reasons,” Samad said. “However, there hasn’t been sufficient education tying the Census to the community’s welfare.”

Dr. Tecoy Porter, Sacramento President of the National Action Network, shares this concern.

“One of the reasons African Americans are undercounted is our household situations. We tend to not want to reveal all of our information or we do not trust the government,” Porter said. “We think that information could be applied against us.”

Hawkins says he understands those fears. However, he believes that they should not prevent people from wanting to be counted.

“Most of the time if a person is skeptical, they won’t fill out the form at all,” Hawkins said. “But the Census information is completely confidential.”

While some experts underscored the importance of an individual selecting a specific race on his or her census questionnaire, others pointed to the significance of participants choosing how they want to identify themselves.

Lanae Norwood, Strategic Communications Director of the California Black Census and Redistricting Hub “My Black Counts,” stated that while educating African Americans on their options when identifying themselves during the 2020 Census is their goal, individual expression is equally important to her organization.

“Our civic engagement program is about educating and encouraging the Black community to be part of the census count. We are not telling Blacks—or anybody for that matter—how to self-identify in the census or what box to check,” Norwood said. “we recognize that Black is not a monolith and contains much racial and ethnic diversity. We trust people to select the racial or ethnic identity that most represents them.”

(Reprinted from the Los Angeles Sentinel)