[Celebrating Juneteenth] History Of Slave Patrols: Early Form Of Police In The U.S.

This is the second of our six-part series ‘Celebrating Juneteenth’ – June 19th is Juneteenth, the oldest known celebration commemorating the ending of slavery in the United States. It is also known as African American Independence Day. Unfortunately, due to the pandemic, the Annual NC Juneteenth Celebration will be not be held in 2020 but will return on June 19, 2021, from 1 pm – 10 pm in downtown Durham. The Celebration is always free and open to the public.

This is the second of our six-part series ‘Celebrating Juneteenth’ – June 19th is Juneteenth, the oldest known celebration commemorating the ending of slavery in the United States. It is also known as African American Independence Day. Unfortunately, due to the pandemic, the Annual NC Juneteenth Celebration will be not be held in 2020 but will return on June 19, 2021, from 1 pm – 10 pm in downtown Durham. The Celebration is always free and open to the public.

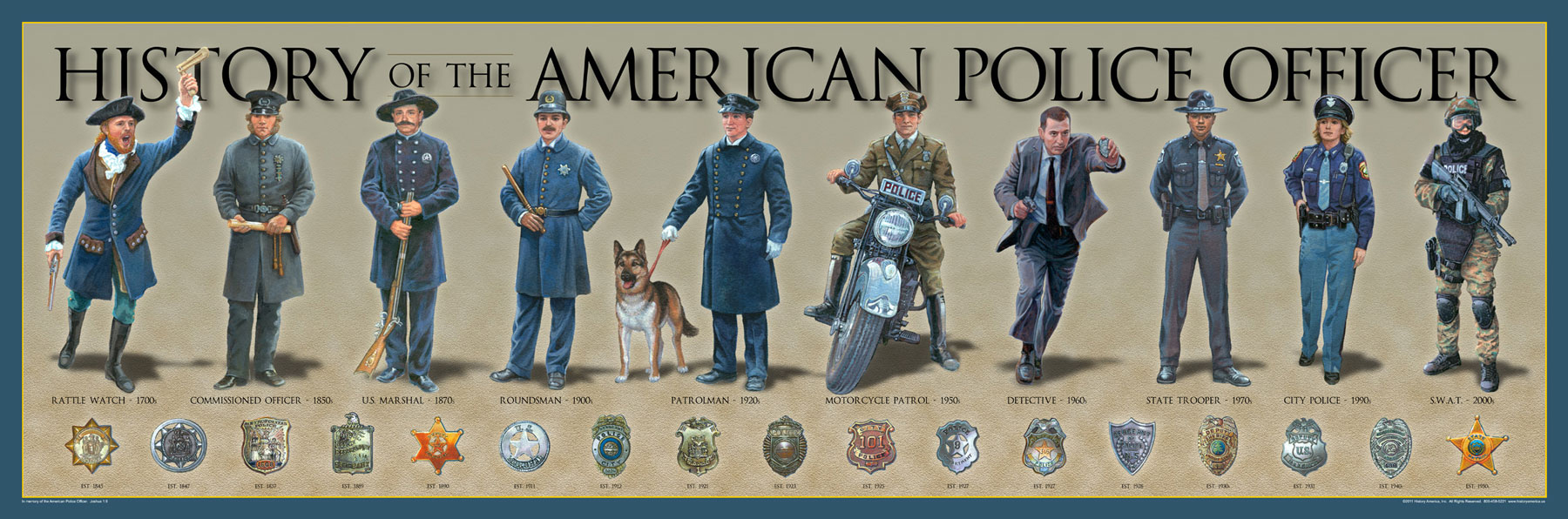

The birth and development of the police in the U.S. can be traced to a multitude of historical, legal, and political-economic conditions. The institution of slavery and the control of minorities, however, were two of the more formidable historic features of American society shaping early policing. Slave patrols and Night Watches, which later became modern police departments, were both designed to control the behaviors of minorities.

“I [patroller’s name], do swear, that I will as searcher for guns, swords, and other weapons among the slaves in my district, faithfully, and as privately as I can, discharge the trust reposed in me as the law directs, to the best of my power. So help me, God.”

-Slave Patroller’s Oath, North Carolina, 1828.

When one thinks about policing in early America, there are a few images that may come to mind: A county sheriff enforcing a debt between neighbors, a constable serving an arrest warrant on horseback, or a sole night watchman carrying a lantern through his sleeping town. These organized practices were adapted to the colonies from England and formed the foundations of American law enforcement. However, there is another significant origin of American policing that we cannot forget—and that is slave patrols.

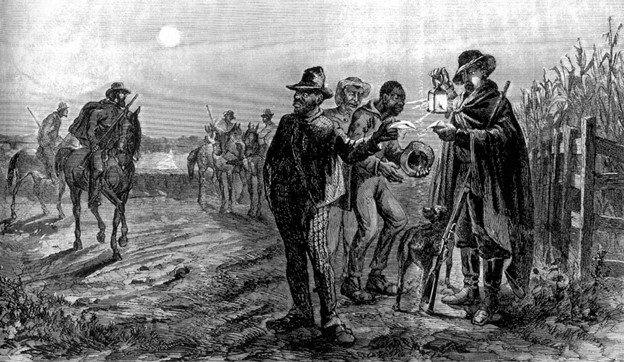

The American South relied almost exclusively on slave labor and white Southerners lived in near-constant fear of slave rebellions disrupting this economic status quo. As a result, these patrols were one of the earliest and most prolific forms of early policing in the South. The responsibility of patrols was straightforward—to control the movements and behaviors of enslaved populations. According to historian Gary Potter, slave patrols served three main functions: (1) to chase down, apprehend, and return to their owners, runaway slaves; (2) to provide a form of organized terror to deter slave revolts; and, (3) to maintain a form of discipline for slave-workers who were subject to summary justice, outside the law.

The American South relied almost exclusively on slave labor and white Southerners lived in near-constant fear of slave rebellions disrupting this economic status quo. As a result, these patrols were one of the earliest and most prolific forms of early policing in the South. The responsibility of patrols was straightforward—to control the movements and behaviors of enslaved populations. According to historian Gary Potter, slave patrols served three main functions: (1) to chase down, apprehend, and return to their owners, runaway slaves; (2) to provide a form of organized terror to deter slave revolts; and, (3) to maintain a form of discipline for slave-workers who were subject to summary justice, outside the law.

Organized policing was one of the many types of social controls imposed on enslaved African Americans in the South. Physical and psychological violence took many forms, including an overseer’s brutal whip, the intentional breakup of families, deprivation of food and other necessities, and the private employment of slave catchers to track down runaways.

Slave patrols were no less violent in their control of African Americans; they beat and terrorized as well. Their distinction was that they were legally compelled to do so by local authorities. In this sense, it was considered a civic duty—one that in some areas could result in a fine if avoided. In others, patrollers received financial compensation for their work. Typically, slave patrol routines included enforcing curfews, checking travelers for a permission pass, catching those assembling without permission, and preventing any form of organized resistance. As historian Sally Hadden writes in her book, Slave Patrols: Law and Violence in Virginia and the Carolinas,

Slave patrols were no less violent in their control of African Americans; they beat and terrorized as well. Their distinction was that they were legally compelled to do so by local authorities. In this sense, it was considered a civic duty—one that in some areas could result in a fine if avoided. In others, patrollers received financial compensation for their work. Typically, slave patrol routines included enforcing curfews, checking travelers for a permission pass, catching those assembling without permission, and preventing any form of organized resistance. As historian Sally Hadden writes in her book, Slave Patrols: Law and Violence in Virginia and the Carolinas,

“The history of police work in the South grows out of this early fascination, by white patrollers, with what African American slaves were doing. Most law enforcement was, by definition, white patrolmen watching, catching, or beating black slaves.”

The process of how one became a patroller differed throughout the colonies. Some governments ordered local militias to select patrollers from their rosters of white men in the region within a certain age range. In many areas, patrols were made up of lower-class and wealthy landowning white men alike. Other areas pulled names from lists of local landowners. Interestingly, in 18th century South Carolina, landowning white women were included in the potential list of names. If they were called to duty, they were given the option to identify a male substitute to patrol in their place.

First formed in 1704 in South Carolina, patrols lasted over 150 years, only technically ending with the abolition of slavery during the Civil War. However, just because the patrols lost their lawful status did not mean that their influence died out in 1865.

First formed in 1704 in South Carolina, patrols lasted over 150 years, only technically ending with the abolition of slavery during the Civil War. However, just because the patrols lost their lawful status did not mean that their influence died out in 1865.

In fact, it can be argued that extreme violence against people of color became even worse with the rise of vigilante groups who resisted Reconstruction. Because vigilantes, by definition, have no external restraints, lynch mobs had a justified reputation for hanging minorities first and asking questions later. Because of its tradition of slavery, which rested on the racist rationalization that Blacks were sub-human, America had a long and shameful history of mistreating people of color, long after the end of the Civil War.

Perhaps the most infamous American vigilante group, the Ku Klux Klan started in the 1860s, was notorious for assaulting and lynching Black men for transgressions that would not be considered crimes at all, had a White man committed them. Lynching occurred across the entire county not just in the South. Finally, in 1871 Congress passed the Ku Klux Klan Act, which prohibited state actors from violating the Civil Rights of all citizens in part because of law enforcements’ involvement with the infamous group. This legislation, however, did not stem the tide of racial or ethnic abuse that persisted well into the 1960s.

Perhaps the most infamous American vigilante group, the Ku Klux Klan started in the 1860s, was notorious for assaulting and lynching Black men for transgressions that would not be considered crimes at all, had a White man committed them. Lynching occurred across the entire county not just in the South. Finally, in 1871 Congress passed the Ku Klux Klan Act, which prohibited state actors from violating the Civil Rights of all citizens in part because of law enforcements’ involvement with the infamous group. This legislation, however, did not stem the tide of racial or ethnic abuse that persisted well into the 1960s.

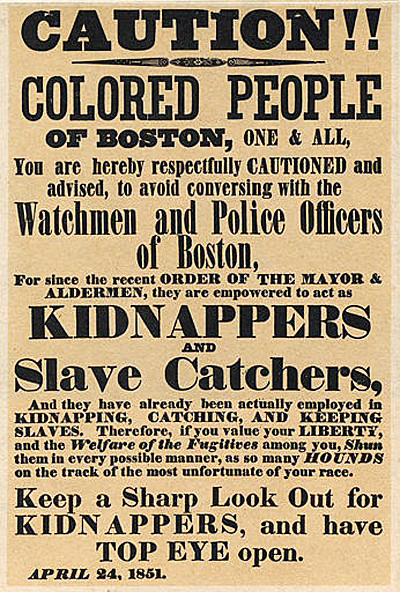

Policing was not the only social institution enmeshed in slavery. Slavery was fully institutionalized in the American economic and legal order with laws being enacted at both the state and national divisions of government. Virginia, for example, enacted more than 130 slave statutes between 1689 and 1865. Slavery and the abuse of people of color, however, were not merely a southern affair as many have been taught to believe.

Policing was not the only social institution enmeshed in slavery. Slavery was fully institutionalized in the American economic and legal order with laws being enacted at both the state and national divisions of government. Virginia, for example, enacted more than 130 slave statutes between 1689 and 1865. Slavery and the abuse of people of color, however, were not merely a southern affair as many have been taught to believe.

Connecticut, New York, and other colonies enacted laws to criminalize and control slaves. Congress also passed fugitive Slave Laws, laws allowing the detention and return of escaped slaves, in 1793 and 1850. As Turner, Giacopassi, and Vandiver remark, “the literature clearly establishes that a legally sanctioned law enforcement system existed in America before the Civil War for the express purpose of controlling the slave population and protecting the interests of slave owners. The similarities between the slave patrols and modern American policing are too salient to dismiss or ignore. Hence, the slave patrol should be considered a forerunner of modern American law enforcement.”

Though having white skin did not prevent discrimination in America, being White undoubtedly made it easier for ethnic minorities to assimilate into the mainstream of America. The additional burden of racism has made that transition much more difficult for those whose skin is black, brown, red, or yellow. In no small part because of the tradition of slavery, Blacks have long been targets of abuse. The use of patrols to capture runaway slaves was one of the precursors of formal police forces, especially in the South.

This disastrous legacy persisted as an element of the police role even after the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. In some cases, police harassment simply meant people of African descent were more likely to be stopped and questioned by the police, while at the other extreme, they have suffered beatings, and even murder, at the hands of White police. Questions still arise today about the disproportionately high numbers of people of African descent killed, beaten, and arrested by police in major urban cities of America.

This disastrous legacy persisted as an element of the police role even after the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. In some cases, police harassment simply meant people of African descent were more likely to be stopped and questioned by the police, while at the other extreme, they have suffered beatings, and even murder, at the hands of White police. Questions still arise today about the disproportionately high numbers of people of African descent killed, beaten, and arrested by police in major urban cities of America.