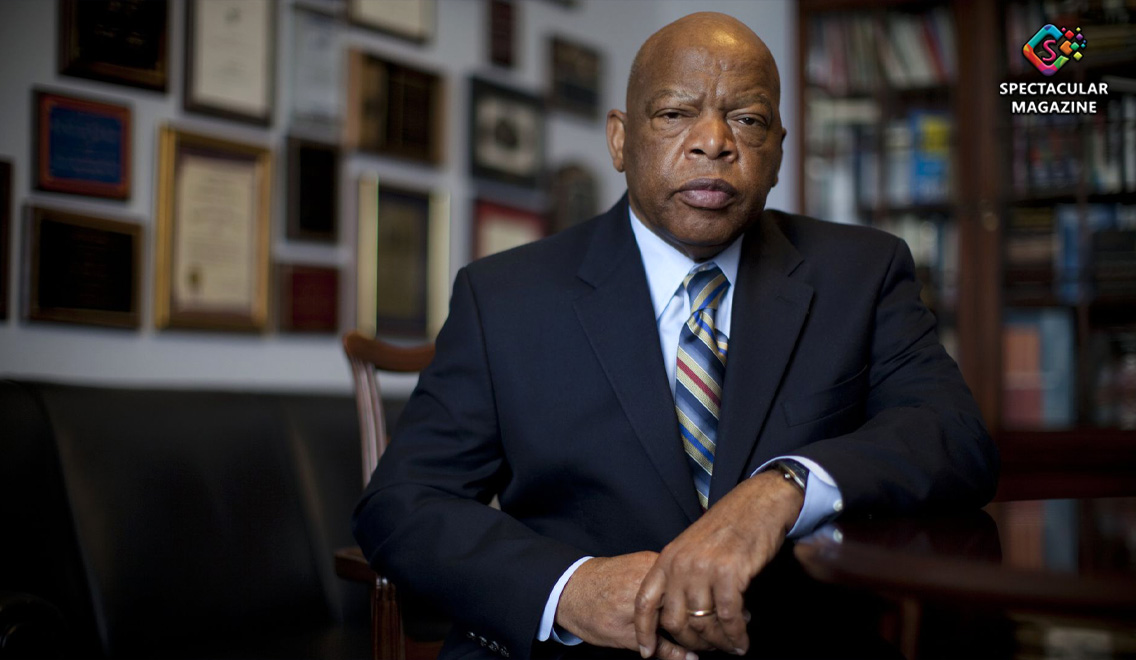

Congressman John Lewis, Iconic Civil Rights Leader, Dies At 80

John R. Lewis, a civil rights leader who preached nonviolence while enduring beatings and jailings during seminal front-line confrontations of the 1960s and later spent more than three decades in Congress defending the crucial gains he had helped achieve for people of color, has died. He was 80.

Mr. Lewis, a Georgia Democrat, announced his diagnosis of pancreatic cancer on Dec. 29 and said he planned to continue working amid treatment. “I have been in some kind of fight — for freedom, equality, basic human rights — for nearly my entire life,” he said in a statement. “I have never faced a fight quite like the one I have now.”

His last public appearance came at Black Lives Matter Plaza with D.C. Mayor Muriel E. Bowser (D) on a Sunday morning in June, two days after taping a virtual town hall online with former president Barack Obama.

While Mr. Lewis was not a policy maven as a lawmaker, he served the role of conscience of the Democratic caucus on many matters. His reputation as keeper of the 1960s flame defined his career in Congress.

When President George H.W. Bush vetoed a bill easing requirements to bring employment discrimination suits in 1990, Mr. Lewis rallied support for its revival. It became law as the Civil Rights Act of 1991. It took a dozen years, but in 2003 he won authorization for construction of the National Museum of African American History and Culture on the Mall.

Mr. Lewis’s final years in the House were marked by personal conflict with President Trump. Russia’s interference in the 2016 election, Mr. Lewis said, rendered Trump’s victory “illegitimate.” He boycotted Trump’s inauguration. Later, during the House’s formal debate on whether to proceed with the impeachment process, Mr. Lewis had evinced no doubts: “For some, this vote might be hard,” he said on the House floor in December 2019. “But we have a mandate and a mission to be on the right side of history.”

Born to impoverished Alabama sharecroppers, Mr. Lewis was a high school student in 1955 when he heard broadcasts by the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. that drew him to activism.

Mr. Lewis vaulted from obscurity in 1963 to head the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, which he helped form three years earlier. SNCC, pronounced “snick,” had quickly become a kind of advance guard of the movement, helping organize sit-ins and demonstrations throughout the South.

Within weeks of taking over SNCC, Mr. Lewis was in the Oval Office with five nationally known black leaders, including King, Whitney Young, A. Philip Randolph, James Farmer, and Roy Wilkins.

Labeled the “Big Six” by the press, they rejected President John F. Kennedy’s request to cancel the March on Washington planned for that August that promised to lure hundreds of thousands of protesters to the doorstep of the White House to push for strong civil rights legislation. The president argued that the march would inflame tensions with powerful Southern politicians and set back the cause of civil rights.

From the steps of the Lincoln Memorial, King delivered his aspirational “I Have a Dream” speech. Mr. Lewis, at 23 the youngest speaker, gave a prescient warning: “If we do not get meaningful legislation out of this Congress, the time will come when we will not confine our marching to Washington. . . . We must say, ‘Wake up, America, wake up!’ For we cannot stop, and we will not be patient.”

The toughest of the major addresses, Mr. Lewis’s text had been toned down earlier that day at the behest of his seniors — including King, his mentor. They feared that explicit condemnation of the Kennedy administration’s timidity and the threat of a “scorched earth” approach would create a political backlash. (With the death of Mr. Lewis, all of the speakers from the March are now deceased.)