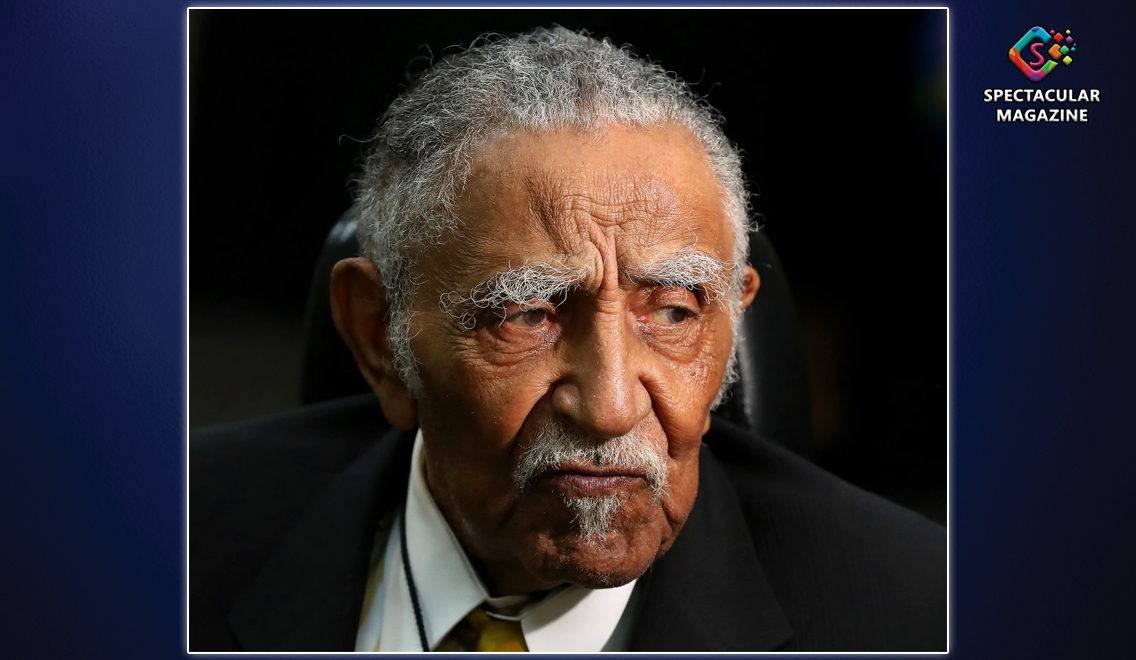

Rev. Joseph Lowery, Civil Rights Icon, Dies At 98

Atlanta, GA – Rev. Joseph E. Lowery, a civil rights leader who was among the prominent ministers who founded the Southern Christian Leadership Conference with the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. and later served as the group’s president for 20 years, died March 27 at his home in Atlanta. He was 98.

His family announced his death in a statement. The cause was not disclosed, but his family said it was not related to the coronavirus outbreak.

The Rev. Lowery’s civil rights work began in the late 1950s when he helped start the SCLC, a nonviolent, civil disobedience organization. He was a member of the SCLC board and traveled often to meet with King and other leaders to help steer the organization, providing advice and participating in protests at the height of racial unrest in the South.

In 1963, a last-minute decision to take a late-night train home to Nashville to see his wife saved Rev. Lowery’s life. The Birmingham, Ala., hotel room that King had offered him that night was bombed. No one was killed, but Rev. Lowery often recalled how close he came to dying. He later used that and other near-death experiences to describe himself and other participants in the civil rights movement as “a little crazy, good crazy,” willing to risk their lives to shake up the segregated South and usher in equal rights for blacks.

Often working in the background, Rev. Lowery adopted a higher profile in March 1965, at the end of the five-day, 54-mile “Bloody Sunday” march for voting rights from Selma to Montgomery, Ala. After the march, he became chairman of a committee appointed to take protesters’ demands to Alabama’s segregationist governor, George Wallace.

Rev. Lowery described walking to the State Capitol steps and seeing a sea of blue-uniformed state troopers standing in front of the governor’s office. The National Guard was there too, authorized to protect Rev. Lowery. The guardsmen tramped in front of the state troopers and Rev. Lowery passed through.

Rev. Lowery was also one of the four black ministers sued in the seminal case of New York Times Co. v. Sullivan (1964), in which an Alabama official accused the newspaper and the civil rights leaders of libeling him in an advertisement. The ad was intended to raise funds for King’s defense against felony charges related to his 1956 and 1958 Alabama tax returns, but the lawsuit caught Lowery by surprise. He and the other defendants had not been informed that their names would be used in the ad.

An all-white jury initially ordered the ministers to pay $500,000 each. Rev. Lowery’s 1958 Chrysler Imperial sedan and other property were seized in Mobile, Ala., and sold at a state-ordered auction. The U.S. Supreme Court eventually vindicated the ministers in a landmark ruling and set a higher standard in defamation lawsuits by establishing the precedent that public officials must prove that a defendant knowingly and maliciously made false statements about them.

Rev. Lowery’s stature and reputation grew as he outlived many other civil rights leaders. Following King’s assassination in 1968, the SCLC became rudderless and beset with infighting. By the time Rev. Lowery was elected SCLC president in 1977, the organization was $10,000 in debt and membership had fallen drastically.

Rev. Lowery raised money and returned the organization to solvency while focusing it on a new set of civil rights issues.

He described his busy years at the helm of SCLC to Ebony magazine: “First we went to Mississippi and jumped on the Southern Company for buying coal from South Africa. Then we went to North Carolina and marched for Ben Chavis. Next, we went to Decatur, Ala., for Tommie Lee Hines.”

Chavis was part of the so-called Wilmington Ten, whose members were arrested in 1972 in North Carolina and convicted of conspiracy to murder charges. He and the others spent nearly a decade in jail.

Hines was a mentally disabled black youth charged in 1979 with raping a white woman in Decatur. Rev. Lowery and hundreds of people marching in support of Hines were fired upon by a group of robed Klansmen when they entered the white side of town. Rev. Lowery and his wife, Evelyn, escaped the barrage of bullets shaken but without a scratch; a few marchers were injured but none critically. The SCLC held a second march in the town a week later that drew 4,000 protesters. An all-white jury initially convicted Hines, but on appeal a year later he was found incompetent to stand trial and was released.

Much of Rev. Lowery’s work in the 1980s and 1990s never made headlines, which chafed him. He often said the media thought “the movement died with Martin.” Rev. Lowery retired from the SCLC presidency in 1997 but became known as the dean of the civil rights movement and was a revered authority on its legacy. He preached often, shook hands and posed for photos after sermons, even as he grew frail. His messages from the pulpit often centered on King and the struggle for black rights.

“They have made Martin a glorified social worker, and they have almost made our young folks believe that all Martin did was go around dreaming,” Rev. Lowery told members of an Atlanta church before a King holiday celebration in 2008. “He was a nonviolent militant. He was a Christian radical.”

Late in his life, Rev. Lowery returned to the news pages when he became a vigorous supporter of Barack Obama, who chose Rev. Lowery to deliver the benediction at his presidential inauguration in 2009. Rev. Lowery said he saw in Obama a young man whose words tapped into the heartbeat of the people — just like the well-known speeches of the civil rights movement. Obama presented the Presidential Medal of Freedom to Rev. Lowery in 2009.

Aside from his life’s work as a civil rights agitator, Rev. Lowery pastored Methodist churches for nearly 50 years.

Joseph Echols Lowery was born Oct. 6, 1921, in Huntsville, Ala., and grew up within steps of a Methodist church. His father owned small businesses and his mother taught school part-time. His mother insisted that he attend church, sing hymns and make speeches before the congregation, he recalled.

“I went to church so much, I swore once I got grown I would never go back to church, [but] the church became a part of me,” he said in an interview.

His childhood was also his introduction to Southern racism. The summer he was 14 he entered his father’s store to get some candy. As he left the store, a large white policeman hit him in the stomach with a nightstick and said, “Get back boy, don’t you see a white man coming in?”

He ran home to get his father’s pistol, intent on challenging the officer. His father, who was usually not home in the middle of the day, providentially came home and stopped his son. After the incident, Rev. Lowery vowed to fight prejudice when he grew up.

He graduated in 1943 from Paine College in Augusta, Ga., with a bachelor’s degree in sociology. For a time, he worked as a journalist in the black press, but he soon decided to become a minister. He attended Paine Theological Seminary and in 1948 accepted his first pastorate in Birmingham, where he met his future wife, Evelyn Gibson. She died in 2013.

Survivors include three daughters from that marriage and two sons from a previous marriage, which ended in divorce, to Agnes Moore.

Rev. Lowery retired as a pastor in 1992 but remained a busy speaker and preacher unafraid to use his place behind the pulpit to make political rebukes. In 2006, at the funeral of Coretta Scott King, Rev. Lowery decried the Iraq War as President George W. Bush sat a few feet behind him. Bush hugged Rev. Lowery as he left the pulpit and the minister later said his intention was to offer a loving correction in the tradition of the black church.

“I think Joe always believed like [King] did, that his purpose was to speak the polite truth as he sees it, irrespective of political calculation and social niceties,” civil rights historian David Garrow said.